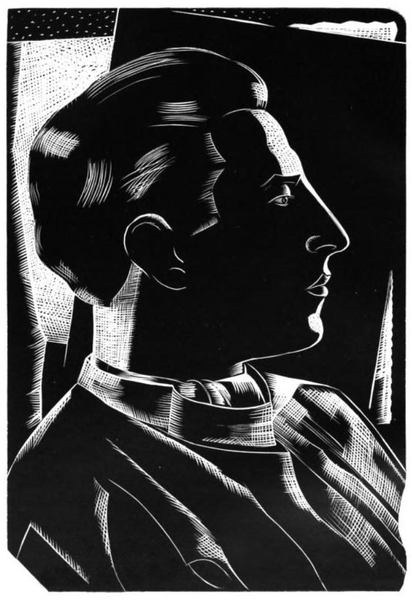

Paul Nash – Life and Works

kjs on 27th May 2022

Brief Introduction on Paul Nash

Paul Nash created extremely beautiful and lyrical landscapes that were delicately re-imagined via elements of modernism and the horrifying realities of war.

He was a busy and enormously gifted artist, writer, photographer, illustrator, designer of theatre settings, fabrics, posters, and, most notably, painter.

There is something characteristically English in Paul Nash’s work, with its sentimental connection to the countryside, constantly subdued romance, and concern in the perpetual cycle of time.

He is related to a lineage of English Romantic poets and landscape painters, most prominently William Blake and J.M.W. Turner. He was also fascinated by artists Samuel Palmer and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and he, like the others, was successful in bringing English art to the global platform.

Despite his embrace and incorporation of many key twentieth-century art styles, such as Surrealism and abstraction, Nash’s profound passion for nature and the surrounding terrain continued to be the principal theme of his work.

Even while documenting the wreckage of battlefields and getting traumatized by the destruction that he witnessed as an official war artist during both great wars, he succeeded in making everything he depicted appear somehow captivating.

Thus, Nash provides his audience a wonderful insight— the understanding that even death brings life and that the imagination always alters, even the most dreadful images.

Artistic Endeavor

Abstract Landscape

Landscape by Paul Nash – Stretched Canvas

Paul Nash, a British painter, rarely addresses abstract art discussions. However, his Modernist, sometimes surreal paintings provide glances of the deep abstract truths that hide in the natural world.

Before and especially during World War II, he produced a body of work that could be described as conservative in its use of abstract language.

In order to construct a larger notion of abstraction, he turned to the classic, figurative landscape rather than pure abstraction or the exploration of formal abstract elements like color, line, or light.

Rather than depicting landscapes, he believed his paintings would provoke thoughts about the eternal connections between time, nature, people, culture, and death.

Nash’s depictions of battle are uncompromisingly realistic. Yet, beyond their metaphorical content, they have clear conceptual levels. While on the surface, the picture Spring in the Trenches (1917-1918) depicts a group of troops in a battle-scarred natural setting, it is actually a metaphor for the horrors of war.

While we may be able to destroy nature with our hatred momentarily, nature will outlast our wrath and continue after we are gone, as seen by the soft color scheme, carefree birds, and innocently wandering white clouds.

Blue Trees

Nash is arguably one of the most intriguing British landscape painters of the 20th century, renowned for his depictions of the “spirit” of Avebury, Wittenham Clumps, and other English locations with which he felt a strong, almost mystic connection.

As a study of beech trees and chalklands, Wood on the Downs (1929), which has been reprinted numerous times since it was first shown, has been a tremendously popular piece of art.

Through the use of natural elements like trees, trails, birds, and hills, he was able to convey a profound sense of connection to the English countryside in a fresh and cutting-edge manner.

Landscape from a Dream

Nash’s unique approach to Surrealism, a movement he had been following since the 1920s, is often seen in this picture as its zenith. Inspired by the Surrealists’ fascination with Freud and their views on the power of dreams, this painting was completed soon after Nash visited the International Surrealist Exhibition in 1938. At the time, Nash befriended Eileen Agar, who was also a surrealist artist.

The painting portrays a hawk looking into a mirror, which also reveals a landscape and various other spheres. The action takes place on the Dorset coast; however, it is confined to the space between two screens.

The painting’s overall impression is both disturbing and intriguing because of the odd activity in the painting’s center and the familiar surroundings beyond it.

There is a lot in the similarity between the way dreams combine the known and unforeseen in this way. Each of the painting’s aspects was later explained by Nash, who said the hawk represents the physical world, while the spheres represent the soul.

Mineral Objects (1935)

While in England in 1933, Nash visited Avebury in Wiltshire. “Excited and fascinated,” he said, by the Neolithic structures and standing stones he discovered there, where “magic” and “sinister beauty” coexisted in perfect harmony.

He painted the area multiple times, and each time emphasizing a different aspect of the eerie atmosphere he felt while visiting the location. Mineral Objects is one of the significant pieces of his “Megalith Series”.

This piece of art is about the dual appeal of the monuments, which have both an outstanding age value and the ability to depict past generations: “lines, masses and planes, directions, and volume”.

The artist saw a mystical quality in the history and geometry of these stones.

While Nash’s past war paintings are marked by anarchy, wreckage, and turmoil, this might be an intentional antithesis, an attempt to restore harmony and balance through the medium of art.

Trees in Bird Garden, Iver Heath (1913)

If we take a closer look at Paul Nash’s Trees in Bird Garden, it’s clear that he wasn’t content to paint realistic depictions of specific locations in space and time.

Nature’s serenity and death’s horrifying beauty also inspired him to create the landscapes of his mind. Even when the spirit of a place was plainly wicked, he was able to capture its genius loci.

Nevertheless, as he once stated, “to find, you must be able to perceive. There are places, just as there are people and objects, whose relationship of parts creates a mystery.”

Among his depictions of life and death, juxtaposing modern artifacts with those from ancient civilizations, there is a hidden connection; a connection that serves as a reminder that history predates and will outlast us and that despite our connection to nature, we cannot defeat nature; rather, nature waits patiently for us to be defeated.